Bad survey quality is annoying. To know how to improve it, let's get discerning about what we mean by "low quality" responses.

Response quality is an ongoing issue for the market research industry. Sometimes it’s easy to spot sample that looks incorrect, but it’s not always easy to say “why” it’s incorrect. This article aims to help clarify what we mean by “low quality” responses.

What is good sample?

Let’s start with the inverse question: what is a “good” sample? Good sample is, broadly speaking, a sample that is externally valid, i.e. one that allows us to make inferences about the population you are interested in the context of the research question you are asking. That typically means:

- The sample is large enough to make inferences about the population.

- The sample is representative of the population you are interested in.

- The response people give are accurate and truthful.

We are particularly interested in the last two points. The first one is a matter of sample size, which is a separate issue.

Classification of quality issues

Sample quality issues can be classified into two categories: sample-level issues and response-level issues.

Sample-level issues

Sample-level issues are those that affect the entire sample, such as:

- Non-representative sample: The sample is not representative of the population you are interested in. This can happen for these reasons:

- Insufficient coverage: The sample does not cover the entire population you are interested in. For example, you are surveying people in the US, but your sample only includes people from California.

- Quota issues: The sample does not meet the quotas you set. For example, you want to survey general population, but your sample is skewed towards young people.

- Wrong people in sample: The sample includes people who are not part of the population you are interested in. For example, you are surveying people in the US, but your sample includes people from Canada.

- Supplier fraud, which unfortunately is not uncommon in the industry.

The causes of these issues include:

- Non-response bias: The people who respond to the survey are different from those who do not respond. This is a common issue in online surveys where people self-select to participate via online panels.

- Non-completion bias: The people who complete the survey are different from those who do not complete the survey. This can happen because of survey fatigue, survey length, or survey design.

- Quick fills: Some groups of people are more likely to be on online panels. In most markets, there are more women than men responding to surveys. If quotas are not set, the sample will be skewed towards female respondents.

- Old or inaccurate profiling data: This is very common for topics such as maternity and pregnancy where the respondent’s profile changes rapidly. If sample selection only relies on profiling data without screening questions, the sample composition will be unrepresentative of the desired population.

- Mistakes in sampling, which happen occasionally (perhaps one percent of the time) and can be due to human error or technical issues.

Response-level issues

There are broadly two types of response-level issues: when respondent should not be in the sample and when it’s the right respondent, but their response is unusable in research.

When respondent should not be in the sample

- Those generated by bots, including:

- Responses by AI agents,

- Bots that aim to generate income from sample providers,

- Bots that scrape surveys for information about new products,

- Bots that aim to destabilise the research process or a platform.

- Click farms or survey farms, where people (often well-equipped with multiple devices) are paid to answer surveys.

- Opportunistic respondents who do not qualify for the survey but want to make money or points from the survey reward and find their way through the screener (by guessing what sample you are after).

- Duplicates (i.e. respondents who take the survey multiple times).

When responses from qualifying people are unusable in research

- Not enough attention

- Respondent’s technology issues

- Respondent misunderstands the survey questions

- Respondent’s dishonesty

- Occasionally slip of the pen

All these issues can be driven by the respondent and by the survey design:

| Issue | Respondent-driven | Survey design-driven |

|---|---|---|

| Not enough attention | They are not in the mood, are tired, not interested in the topic | The survey is too long, the questions are too complex |

| Respondent’s technology issues | They are on an old mobile device, they have distracting plugins | The survey is too slow to load, the survey is not mobile-optimised |

| Respondent misunderstands the survey questions | They are not native speakers of the survey language, they are not familiar with the survey topic | The questions are too complex, the questions are not clear |

| Respondent’s dishonesty | They want to finish the survey quickly, being there just for the reward | The survey is asking inconvenient questions |

| Occasional slip of the pen | It can happen to anyone and it increases with fatigue | The survey is too long, the questions are too complex |

What low quality responses are not

Responses that do not match the hypothesis of the researcher are not low quality in and of themselves. In fact, these are often the most useful responses because they help us understand the limits of our hypotheses.

However, of course, it’s always worth checking those for any response quality issues.

Patterns of low quality responses

Here are some characteristics we use to identify potentially low-quality responses:

- Nonsensical, gibberish or off-topic answers to open-ended questions

- Copy-pasting answers from external sources, such as Wikipedia or ChatGPT

- Speeding through the survey

- Straight-lining, i.e. selecting the same answer for all questions in a grid

- Respondents that give the same open-ended answers to questions in a row

- Failing checks for extreme acquiescence bias

- Contradictory answers to related questions

- Failing trap questions

- Location mismatch

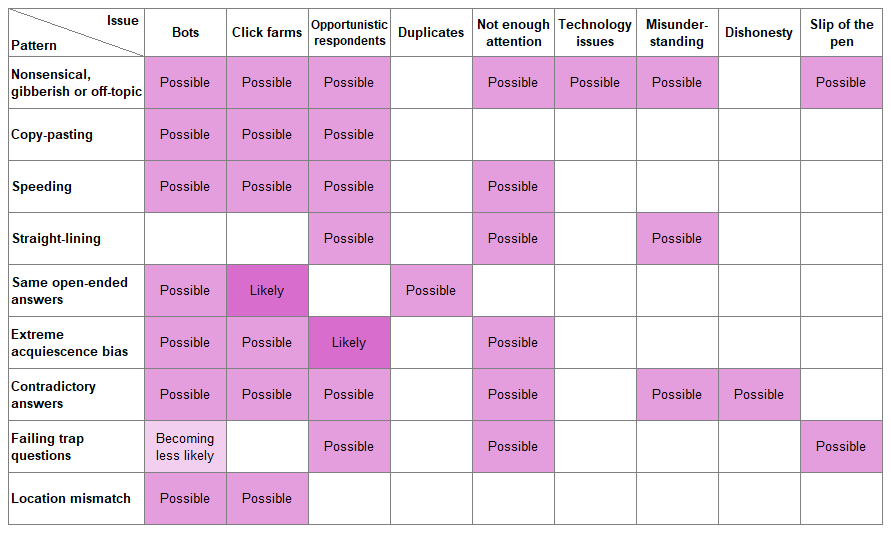

The table below shows correspondence of these patterns to response-level quality issues:

This is not an exhaustive list: the platform automatically checks for more than these. As you see from the table above, each pattern can be caused by multiple issues, and each issue can manifest in multiple patterns.

At the same time, it is not guaranteed that responses with these characteristics are low quality. We recommend treating these as red flags that warrant further review.

Points of caution on these patterns

Most of the time, nonsensical, gibberish or off-topic answers are a sign of response quality issues. Yet, occasionally, off-topic answers are a way for the respondent to avoid answering an uncomfortable topic. If you see an otherwise fine response, it’s worth considering whether the respondent is trying to avoid a question.

On speeding: Most research clients underestimate the LOI at the stage of survey design (i.e. what is thought to be a 10-minute survey, turns out to have a medial LOI of 20 minutes). But they also underestimate the variance in response speed. Some people are a lot faster at processing information than others. It is normal for some people to finish the survey in half or even quarter the time you expected. When you consider how people make purchase decisions, there is similar variability: some will take a week, others will buy on impulse, which can and often should be reflected in your sample.

While some researchers consider straight-lining a tell-tale sign of low-quality responses, it’s not always the case. Some people may have strong opinions on a topic and consistently select the same answer. If you exclude them from your analysis, you may be excluding valuable data.

Avoid wholesale exclusions of responses based on contradictory answers. People are complex and can hold seemingly contradictory opinions, which can be elicited by different questions. A contradictory opinion can be a sign of unstable beliefs, while contradictory answers to factual questions can indicate memory issues (where it’s best to average or weight the answers rather than discard the response).

Trap questions (e.g. where you instruct respondents to select a particular answer) may be a good way to avoid inattentive respondents, but they can also be a source of bias and annoyance. What’s more, in the age of LLMs and agents, they do not protect from bots or click farms. We recommend using them sparingly.

How Conjointly ensures high survey sample quality

At Conjointly, we combine automatic and manual checks on every project. That means that specifically for Predefined panels our fieldwork team will look through responses at the end of every project to make sure they are good to use and if not, we will aim to rectify this. For Self-serve sample, we provide a range of tools to help you manage response quality, including the ability to exclude low quality responses (up until pausing data collection).