Learn how to design effective surveys for children by understanding cognitive development stages, optimising question formats, and minimising response bias to ensure valid and reliable data collection.

Survey response quality is fundamentally dependent on both validity and reliability. To achieve high-quality responses, respondents typically navigate four distinct cognitive stages: comprehension, retrieval, judgement, and communication. When child respondents successfully progress through all four stages, they produce optimised responses that accurately reflect their true perspectives and experiences.

However, research demonstrates that children frequently engage in satisficing behaviour—selecting the path of least cognitive effort rather than providing thoroughly considered responses. Such satisficing strategies may be precipitated by multiple factors, including inadequate questionnaire design, survey fatigue, or developmental limitations inherent to the child’s current cognitive stage.

This guide outlines best practices to help researchers mitigate developmental barriers and ensure data quality when conducting surveys with children.

Ethical and procedural standards

The MRS Guidelines (2014) [1] mandate strict protocols to protect young participants:

- Researchers must obtain and verify permission from a responsible adult (parent, guardian, or teacher) before a child under 16 participates.

- Even if a parent agrees, the child should be given the opportunity to decline or opt out at any time.

- Research should be conducted in safe venues. For in-home or online research, a responsible adult should remain on the premises.

- Participant anonymity should be preserved unless explicit informed consent is given to reveal details.

Understanding cognitive development

Research design should align with a child’s developmental stage to ensure data quality. According to Borgers, De Leeuw, and Hox (2000) [2], children process information differently as they age:

- Ages 4–8 (Intuitive stage): Children are literal and have limited memory. They may fear giving a “wrong” answer to an adult.

- Example: A 5-year-old might respond “no” to having bought candy in the past 3 months because their parent/guardian buys it for them.

- Ages 8–11 (Concrete operations): Children develop language skills but struggle with abstract concepts and logical forms like negation. They are prone to satisficing effects (choosing an easy, satisfactory answer rather than an optimal one) if they become bored or overwhelmed.

- Example: A 10-year-old might respond with their favourite sweets even if the question is posed as “Which of these is NOT among your favourites?” as they are prone to miss negation.

- Ages 11–16 (Formal thought): Logic is near-adult level, but children are highly sensitive to social context, peer pressure, and the presence of others.

- Example: A teenager might underreport their daily consumption of sweets if their responses are being monitored by their guardian.

Designing effective questions

Selecting the right quantity of options

In multiple-choice questions, children aged 7–10 should be given 3–4 options (or simple yes/no questions), while those 11 and above can handle five options [3].

Prioritising words over numbers

Graded scales using numbers as anchors should be avoided for children, as they do not accurately reflect their internal judgements. Mellor and Moore (2014) [4] found that number-based scales (e.g., 1–5) had very low consistency (less than 35%) with children’s true feelings.

The best format is word-based scales, particularly those reflecting frequency (e.g., never, sometimes, regularly). These show consistency levels of up to 78%.

For example, “How often do you consume sweets?” should have the options “Never”, “Regularly”, “Every day” instead of “Once a week”, “Twice or more a week”.

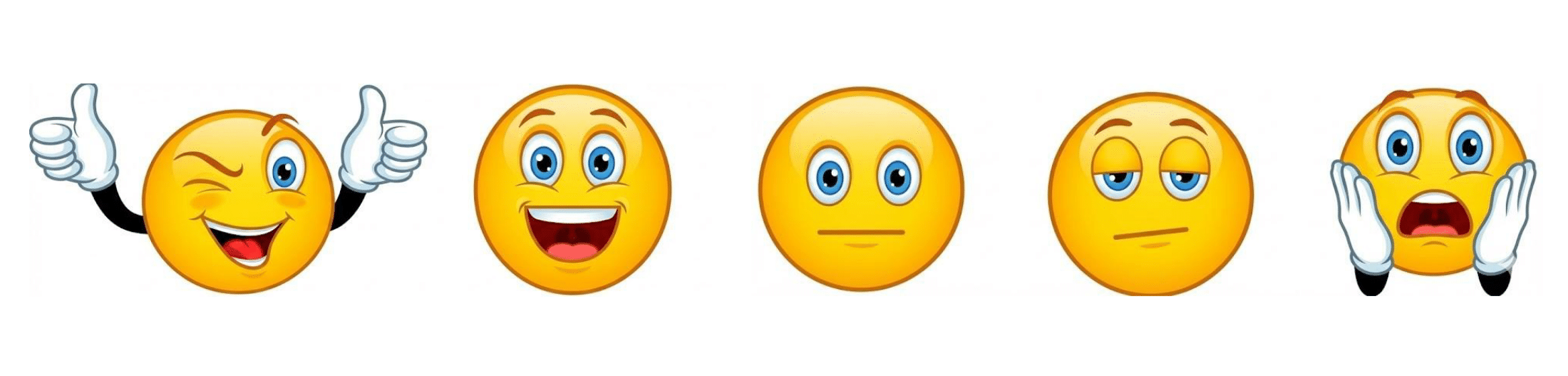

Optimising smiley face Likert (SFL) scales

While engaging (especially compared to text/number options), smiley scales often suffer from positive bias because children avoid “sad” faces when evaluating fun experiences. A child might pick the happier face for a toy because it feels “mean” to select a sad face, even if they don’t necessarily like the toy.

For positive experiences (like sweets or toys), use the “five degrees of happiness” model or a dramatised SFL [5], a scale of five faces ranging from neutral/shocked to very happy.

Each face should be clearly different. Yahaya and Salam (2008) [6] noted that children find “slightly same” faces difficult to distinguish.

Minimising bias and maximising quality

To ensure the data you collect is accurate and unbiased:

- Use short questions and simple sentences, but preambles and introductory text can aid comprehension.

- Example: An intro screen dividing two different types of questions: “The next few questions are about the toys you have at home. There are no right or wrong answers, just tell us what you think.”

- Negation should be avoided. Do not use “not” or negatively phrased questions, as children often misinterpret these.

- Avoid hypothetical questions and indirect wording. Children under 8 take questions very literally.

- Example: Concepts like “brand loyalty” or “value” might be difficult for a 7-year-old to comprehend, yet easier for a 14-year-old.

- Example: “Have you consumed sweets…” instead of “have you purchased sweets…” as children might interpret the question as exclusively buying the sweets themselves.

- Randomisation is highly important as children are prone to response order effects (primacy/recency biases).

- Example: When asked “which one do you like more: the gummies or the lollipops?”, the child might say “the lollipops” simply because of recency bias.

- Children are prone to social desirability biases and may answer in ways they think will please the researcher or their parent/guardian. Remind them there are no wrong answers and they can skip any question (if applicable).

- Suggestion for reducing social desirability: “Some children like to eat lollipops, but other children prefer fruit snacks. Which child is most like you?”

- Long surveys lead to “satisficing” and loss of interest. A 36-question survey is considered too long for primary school children. School climate research suggests that student surveys should be capped at 10 minutes to preserve data quality.

- Response cards or graphical cues act as “external memory” for children, helping them remember their options. The use of too much text should be avoided and should be supported or substituted with visuals if possible.

- Example: When asking about the type of sweets children consume the most, there should be visuals to accompany the types of sweets.

- Do not ask two things at once. Children will usually answer the last thing they hear.

- Use cognitive pre-tests to ask children to explain what they think a question means before the full study begins.

- Example: “If I asked you whether the packaging of these sweets was ‘appealing’, what do you think ‘appealing’ means?”

Key takeaways

Conducting surveys with children requires careful attention to their cognitive development stage, question design, and potential sources of bias. The investment in thoughtful survey design pays dividends in data quality, ultimately leading to more valid and reliable data that accurately reflects children’s perspectives and experiences, and better outcomes for research involving young participants.

Whether you’re researching product preferences, brand perceptions, or consumer behaviour among children, Conjointly can help you design and execute a study that meets the highest methodological standards. Book a call to discuss your objectives and launch your study today.

References

[1] Market Research Society. (2014). MRS guidelines for research with children and young people. Market Research Society.

[2] Borgers, N., De Leeuw, E., & Hox, J. (2000). Children as respondents in survey research: Cognitive development and response quality. Bulletin of Sociological Methodology/Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique, 66(1), 60-75.

[3] Bell, A. (2007). Designing and testing questionnaires for children. Journal of Research in Nursing, 12(5), 461-469.

[4] Mellor, D., & Moore, K. A. (2014). The use of Likert scales with children. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39(3), 369-379.

[5] Hall, L., Hume, C., & Tazzyman, S. (2016). Five degrees of happiness: Effective smiley face Likert scales for evaluating with children. Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children, 311-321.

[6] Yahaya, W. A. J. J. W., & Salam, S. (2008, November). Smiley faces: Scales measurement for children assessment. Paper presented at the 2nd International Malaysian Educational Technology Convention, Malaysia.